At the end of 2018, Kate Bush released freshly remastered editions of her complete catalogue of albums, together with a selection of B-sides and rare tracks. At the same time Faber & Faber published a handsome anthology of her lyrics. For newcomers and devotees alike, both of these treats are highly recommended. The remastered audio is a revelation (the early albums in particular have never sounded richer, warmer and clearer), while the book, with its often surprising juxtapositions of lyrics selected and grouped together by Kate herself, offers an engrossing and rewarding opportunity to become acquainted, or reacquainted, with those beguiling words.

Like many who write from time to time about pop music, I was approached during the run-up to these releases and asked whether I’d like to consider setting down some thoughts about Kate Bush – in my case, for the Winter 2018 edition of Pride Life magazine. I accepted without hesitation. Kate Bush is an artist I’ve adored since childhood, and in my gallery of musical heroes, many of whom seem to begin with the letter B, she stands tall, occupying a pedestal right alongside Bach, Beethoven and Bowie. Even so, I’d never actually written anything about Kate before – and once I’d begun, I found it difficult to stop. Before long, I’d catastrophically overshot the word limit for the Pride Life feature. In the end some heavy pruning got it down to a manageable size, and the magazine was published just before Christmas.

All the same, having written nearly 4000 words instead of the requested 1200, it seemed a shame to waste them. Here, then, with the kind blessing of editor Nigel Robinson and all at Pride Life, is the full-length version of my Kate Bush piece. The Director’s Cut, if you will.

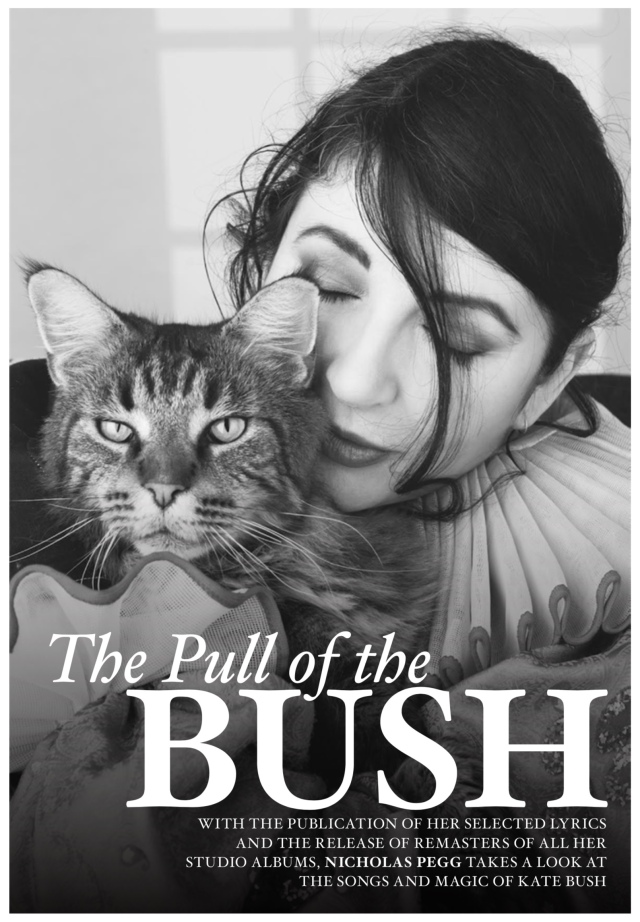

The Pull of the Bush

“I found a book on how to be invisible,” Kate Bush once sang – and now, in a splendidly metatextual flourish, she has published an actual book called How To Be Invisible. Taken from a track on her 2005 album Aerial, the title of Faber’s new anthology of selected lyrics is an appropriate one: not just because Kate Bush famously knows a thing or two about how to be invisible, but also because the song in question encapsulates so much about her art. Slinky and dark, sinister and droll, ‘How To Be Invisible’ is at once a fairytale, a talismanic spell, an ontological reverie on the infinite complexity of existence – and, oh yes, a sublimely beautiful piece of music.

Those of us who love Kate Bush tend to love her with a special kind of devotion, and I’ll put my cards on the table and declare that I love Kate Bush as much as I love any artist who ever drew breath. I was ten years old when ‘Wuthering Heights’ topped the charts in 1978, and no pop singer before or since has ever reached out and grabbed me in quite the same way as that wild-eyed enchantress, so strange and wise and full of secrets. I was bewitched by the poetry and the theatre of it all, the twinkling piano, the strings, the guitars, and the most important instrument of all: that swooping, soaring, spectacular voice. I knew that I had to hear more, and I dropped hints as my eleventh birthday approached. And thus it came to pass that The Kick Inside, Kate Bush’s debut album, was the first proper grown-up LP that I owned.

I don’t suppose my parents knew what lay in store for me on that album: indeed, had they known, they might have thought twice before buying it for a boy of such tender years. But I’ll be forever grateful that they took the plunge, because it’s no exaggeration to say that The Kick Inside blew my eleven-year-old mind. It was vivid and magical and captivating, all the more so because it was smoky and shadowy and elusive. In places I barely understood it at all, but that only added to the fascination. What a peculiar little boy I must have been, lying alone on the living room floor, immersing myself in all that mind-expanding mysticism (“Who’s Gurdjieff?” I casually asked my mother one day), the warm, unfettered femininity (“Every girl knows about the punctual blues” – I knew what that meant, but it was so outside my experience as to be mesmerising), and the subtle agonies which adults seemed to inflict on each other in those mysterious, louche love songs. As for the simmering eroticism (“My stockings fall to the floor, desperate for more”) – well, it was clearly best not to trouble my parents with that sort of thing, so lyrics like ‘Feel It’ and ‘L’Amour Looks Something Like You’ remained a secret between me and Kate. Capping it all was the title track, a suicide note from a woman who has been made pregnant by her own brother. I was only eleven; but the astonishing thing is that the sorceress singing these eerie, enthralling songs to me was only nineteen.

Like every great artist, Kate Bush has tended over the years to explore and re-explore her own particular territory. From The Kick Inside to Hounds of Love to 50 Words for Snow, the modes of expression may have evolved and matured, but the themes and motifs remain remarkably consistent. Items on the agenda in a typical Kate Bush lyric might include sexuality, classical mythology, femininity, Biblical allusion, puberty, self-actualization, our relationship with nature, reaching out for the unreachable, and the possibility of discovering the divine in the everyday. If this all sounds a bit heavy, an abiding wonder of Kate’s work is the miraculous lightness of touch with which she spins it all together. Alight, for example, on ‘Suspended in Gaffa’, a track from her 1982 avant-garde masterpiece The Dreaming, which manages to tackle all of the above topics in a little under four minutes while remaining the prettiest, bounciest, loveliest pop song you could hope to hear.

Kate’s songwriting has always moved fluidly between the abstract and the narrative: on The Dreaming as on all her albums, esoteric philosophical investigations like ‘Gaffa’ rub shoulders with impressionistic vignettes and straightforward short stories, all of them dripping with implication in their own different ways. The title track addresses the plight of indigenous Australians at the hands of white men; ‘Houdini’ finds the escapologist’s widow trying to contact him at a séance; ‘Pull Out The Pin’ eavesdrops on the emotions of a Viet Cong soldier going into battle; ‘Leave It Open’ is a turbulent meditation on the challenge of keeping our minds receptive to stimulus; and ‘Get Out Of My House’ is a frenzied labyrinth of metaphor which rebuilds its emotionally damaged narrator as a shuttered, besieged house, obsessively repelling intrusion by the outside world.

These are the kinds of wild abstractions you can expect to find in a Kate Bush lyric – and not only there. A significant part of her genius lies in the way the lyrics are burnished and expanded by the music, and by the baroque, multi-layered complexity for which her recordings are famed: the immersive jungle soundscape of ‘Pull Out The Pin’, the Australian outback vibe of ‘The Dreaming’, or the exquisitely governed sonic chaos of ‘Get Out Of My House’ are cases in point. But there are other, calmer currents too: a Keatsian insistence on the beauty of truth and the truth of beauty, bound up in a comprehensive awareness of the literary, poetic and musical traditions to which Kate Bush is heir. Amid the exotic trips to Egypt, Malta and Baghdad, there’s no shortage of Englishness: her lyrics brim with Shakespeare, Delius, Peter Pan, Tennyson, summer afternoons, trees, birds and flowers (‘Night Scented Stock’, a wordless vocal confection on 1980’s Never For Ever, celebrates one of the quintessential flowers in the traditional English garden). And then, of course, there’s a certain Emily Brontë novel.

Literature, music and art are Kate’s constant companions. ‘An Architect’s Dream’ marvels at the craft of the painter; ‘Violin’ pays tribute to Paganini and features one of Kate’s most remarkable vocals, impersonating the squeals and swoops of a fiddler’s bow with acrobatic dexterity; ‘December Will Be Magic Again’ – surely the greatest Christmas pop song ever – tips its hat to Oscar Wilde; and ‘The Sensual World’ is a gorgeous adaptation of Molly Bloom’s closing soliloquy from James Joyce’s Ulysses. The literature, music and folklore of Ireland loom large: born to an English father and an Irish mother, Kate grew up surrounded by folksong and fairytale, by the fiddles, bodhráns and uilleann pipes that would later enrich her music.

The appropriation of that famously sensual passage from Ulysses highlights the theme which, more than any other, runs like a seam of gold through the entire Bush oeuvre. “The more I think about sex, the better it gets,” she sings on ‘Symphony in Blue’, and if her lyrics are anything to go by, she thinks about sex a great deal. But this isn’t the saucy seaside postcard sex of repressed curtain-twitchers and sniggering tabloids: this is sex as our profoundest purpose in life, sex as an expression of our deepest emotions, hopes and fears. That’s what we find in the Joycean lovemaking of ‘The Sensual World’, in the marital fairytale of ‘Babooshka’, in the pansexual calypso of ‘Eat the Music’, and in the tender insecurities of ‘Hounds of Love’ and ‘The Man With the Child in his Eyes’. In these and in dozens more, Kate Bush sings at the transformative crossroads where sex meets love, and where we plunge headlong into it all.

Explicit songs of sexual adventure, of which there are many, sometimes veer into transgressive territory. There’s that incestuous pregnancy in ‘The Kick Inside’, inspired in part by the traditional folk ballad of Lizie Wan; there’s ‘Kashka From Baghdad’ on 1978’s Lionheart, which celebrates the joy of a gay couple at a time when most artists were still steering clear of such subject matter; and from the same album, ‘Wow’ has that celebrated innuendo about “hitting the Vaseline”. Most startling of all her taboo songs is ‘The Infant Kiss’ from 1980’s Never For Ever: referencing Henry James’s novella The Turn of the Screw via a famously unsettling scene in its 1961 film adaptation The Innocents, the song bristles with febrile tension as its protagonist wrestles with her inappropriate feelings for a young boy.

Here is as good a point as any to observe that Kate Bush’s songs are not self-portraits. She’s a storyteller, and has cautioned against interpreting her lyrics as autobiographical, something which ought to be obvious to anyone familiar with the likes of ‘There Goes a Tenner’ (a serio-comic heist caper, delivered in a Cockney accent), ‘Ran Tan Waltz’ (a kitchen-sink comedy in which daddy is left holding the baby while mummy goes out on the lash), ‘Heads We’re Dancing’ (a period piece about an encounter with a charming stranger who turns out to be Adolf Hitler), or ‘Coffee Homeground’ (a delirious murder ballad in Brechtian cabaret style, complete with an outrageous German accent from Kate).

These and dozens more are purposely staged pieces: like one of her idols, David Bowie, Bush’s work thrives on the drama and the distancing of its own strong sense of theatricality. In performance, the effect is heightened by that famously flamboyant physicality, honed by the lessons she took as a teenager with Bowie’s legendary dance and mime teacher Lindsay Kemp, to whom she later dedicated The Kick Inside’s opening number ‘Moving’. Her early videos, and her 1979 concert tour, showcase a visual style that is equal parts student and teacher: those expressively mimetic moves are pure Lindsay Kemp, but it’s Kate herself who provides the dramatic vignettes, the props and business, that persistent mise en scène of shady men in trenchcoats and trilbies who populate the knockabout punch-up of ‘Them Heavy People’ and the shotgun melodrama of ‘The Wedding List’, an unforgettable highlight of her 1979 TV special. That netherworld of gangsters and molls is another motif that keeps resurfacing, from ‘James and the Cold Gun’ to ‘There Goes A Tenner’, from the fugitive aviator in ‘Night of the Swallow’ to the sinister government men who populate the videos of ‘Cloudbusting’ and ‘Experiment IV’.

And what videos they are. Again like Bowie, Bush established herself in the 1980s as a pioneer of rock video as an artform in its own right, a visual experience to expand and illuminate the music. 1985’s ‘Cloudbusting’, a seven-minute epic co-starring Donald Sutherland (and inspired, as is the song, by Peter Reich’s memoir A Book of Dreams, about his childhood relationship with his psychoanalyst father Wilhelm Reich) is perhaps her finest video, although the following year’s ‘Experiment IV’ runs it a close second. A horror film in miniature about a military experiment to create a lethal sound, its eye-catching cast includes Peter Vaughan, Richard Vernon, Dawn French and Hugh Laurie. Kate’s fraternisation with luminaries of the comedy circuit is another longstanding fixture (her deliciously smutty Comic Relief duet with Rowan Atkinson is the stuff of legend, as is her Comic Strip Presents song ‘Ken’, while The Red Shoes is the only album ever to feature Prince and Lenny Henry on the same track) – but ‘Experiment IV’ is no spoof. It’s a masterpiece of Cold War atmospherics, oozing macabre wit and escalating menace right up to the final twist as Kate herself, the deadly sound made flesh, turns to camera and places a nonchalant finger to her lips.

Played straight it may be, but in ‘Experiment IV’ as in all her work, there’s a playfulness which is key: however weighty the topic, there’s always a twinkle in those great big eyes. A government file seen in the ‘Experiment IV’ video reveals that the scientist charged with creating that murderous sound is ‘Professor Jerry Coe’ (geddit?). Kate Bush has always had a taste for the corny pun, whether lyrical (in ‘Hammer Horror’ she sings “I’ve got a hunch that you’re following me, to get your own back on me”) or visual (in the video of ‘The Dreaming’, the line “pull of the bush” is accompanied by Bush being literally pulled to and fro by her dancers). Few songwriters would conceive the notion of constructing a lyric about a girl’s emotional commitment around an extended metaphor in which the heroine is portrayed as an out-of-control car; fewer still would have the audacity to call it ‘Don’t Push Your Foot On The Heartbrake’. The title track of 50 Words for Snow finds guest vocalist Stephen Fry enumerating just that: half a hundred snowy synonyms of escalating daftness, from “blackbird braille” and “phlegm de neige” to “creaky-creaky” and “boomerangablanca”. On ‘Pi’, a celebration of the “circle of infinity”, Kate sings the mathematical constant to its 137th decimal place. In a Kate Bush lyric nothing, however preposterous, is off limits.

Of course, there’s no light without shade, and the shadows here are long ones. Another recurrent theme is grief, particularly the grief of bereavement. In her early work there’s a sense that she is writing about such topics at second hand, imagining herself into the role of a grieving mother in ‘Army Dreamers’, or a ghost looking down on her loved ones in ‘Watching You Without Me’. By the time of 1993’s The Red Shoes, perhaps her most underrated album and certainly her saddest, personal loss has begun to infiltrate the lyrics. The Red Shoes is dedicated to Kate’s mother Hannah, who died during the album’s development, and its standout track ‘Moments of Pleasure’, in which she gently invokes her mother’s words and recalls other departed friends including her longtime guitarist Alan Murphy, is almost unbearably poignant. So, too, is ‘You’re the One’, quite simply the saddest break-up song you’ll ever hear; Kate’s relationship with her long-time partner and bassist Del Palmer had recently ended, and here the loss feels like another bereavement. Twelve years later on Aerial, the pain is less raw but the emotion runs, if anything, even deeper. ‘Mrs Bartolozzi’, at first glance a kooky song about a washing machine, discloses itself upon closer inspection to be a hypnotically moving portrait of a woman grieving for her lover; and ‘A Coral Room’ is one of Kate’s quiet masterpieces, a monumental meditation on the waves of time and the keenly felt absence of her mother.

Family is a crucial element in Kate Bush’s work: her narrative songs might not be autobiographical, but the personal touches are clear. Kate’s brothers have made countless contributions over the years: multi-instrumentalist Paddy plays everything from the sitar on ‘Delius’ to the Madagascan valiha on ‘Love and Anger’, while John’s credits include the sleeve photography for Hounds of Love and the hypnotic narrative voice on ‘Jig of Life’. With exquisite poignancy, Kate enlisted her father to provide the spoken voice on 1989’s ‘The Fog’, a song which uses the image of a parent teaching his daughter to swim (“Just put your feet down, child, cos you’re all grown up now”) as a jumping-off point to address the mingled emotions of pride and loss that come with watching a child fly the nest. Two decades later, Kate duetted with her own son, Albert, on the opening track of 50 Words for Snow: then aged thirteen and singing the role of a snowflake falling to earth, the ephemerality of Albert’s soon-to-break treble intertwining with Kate’s motherly timbre achieves an extraordinary pathos.

That magical, adamantine bond between mother and child is another thread in the tapestry that Kate Bush has been weaving for decades. It’s there on The Kick Inside, not just in the title track but also in the meltingly beautiful ‘Room For The Life’, a meditation on the miracle of motherhood in which Kate hovers like an angel of comfort over every “lady in tears”, wrapping womanhood in its own strength and wonder: “No, we never die for long, while we’ve got that little life to live for”. Explorations of motherhood find new and more complex expressions in ‘Army Dreamers’ and ‘Breathing’, the latter among the most remarkable tracks of Bush’s early period. Part hymn to the bond between mother and child, part Kate’s entry in the roll-call of early eighties pop songs addressing the imminent threat of nuclear armageddon, ‘Breathing’ is sung by an unborn infant in the womb, inhaling her mother’s gift of life and, simultaneously, the deadly fallout that hangs in the poisoned air after a nuclear holocaust. Tender, dramatic, terrible and lovely, ‘Breathing’ is as close as rock music has ever come to touching the pellucid beauty and visionary horror of William Blake’s Songs of Innocence and of Experience.

The impermanence of youth, and the pain of losing the protective embrace of parenthood, are constant themes, from ‘All We Ever Look For’ (“Leave the breast and then the nest and then regret you ever left”) to ‘Mother Stands for Comfort’ (“Mother hides the madman, mother will stay mum”). So too is the simple affirmation of love. Years before her own son was born, another choirboy treble had provided a voice of fleeting innocence on 1982’s ‘All The Love’, a song which Kate explained was about “how we forget to tell people we love that we do love them”. Three years after that, at the end of ‘The Morning Fog’, the track which concludes 1985’s song cycle The Ninth Wave, Kate sang with limpid simplicity: “I’ll tell my father, I’ll tell my mother, I’ll tell my loved one, I’ll tell my brothers, how much I love them.” When she performed The Ninth Wave in its entirety as part of her 2014 live extravaganza Before the Dawn, she updated the lyric to add “I’ll tell my son,” gesturing as she did so to Albert, now sixteen, who was on stage with her. You’ve never heard a reaction like it. I don’t think there was a dry eye in the house.

Talking of Albert, perhaps the least abstract of all Kate’s lyrics is ‘Bertie’, her 2005 encomium to her son, then just seven. Like David Bowie’s ‘Kooks’ or Thin Lizzy’s ‘Sarah’, ‘Bertie’ is a song of such unalloyed loveliness that only the most hard-hearted could fail to be moved; significantly, it also brightens the darker shades of Aerial, countering the desolation of ‘A Coral Room’ and helping to establish the more complex framework of the album’s second half. Subtitled A Sky of Honey, it is perhaps Kate Bush’s greatest achievement to date: a symphony of light and dark, a coming together of all the themes and motifs which had populated her work since its earliest days, and the most extravagant and profoundly imagined yet of her rhapsodies on the transformative power of beauty, sensuality, art and nature. Like the passage of the sun across the sky which links its nine songs, the colours and moods on its canvas are ever-changing, building at last to a mystical, transcendent climax.

One extraordinary moment among many on A Sky of Honey is a short piece called ‘Aerial Tal’ in which Kate duets with a blackbird, mimicking the strophes of its twilight song in perfect unison. Birds feature heavily throughout Aerial, whose sleeve artwork depicts the waveform of a blackbird’s song; and once again, it’s a fascination which echoes throughout Kate’s earlier work. “I turn into a bird,” she fantasises in ‘Get Out Of My House’; “Help this blackbird, there’s a stone around my leg!” she howls in ‘Waking the Witch’; “Would you break even my wings?” she demands in ‘Night of the Swallow’; “Who knows who wrote that song of summer that blackbirds sing at dusk?” she muses in ‘Sunset’. From the bird-infested sleeve of Never For Ever to the “blackbird braille” in ‘50 Words For Snow’, and from the “many birds” in the chorus of the newly released rarity ‘Humming’ to the dying blackbird in the video of ‘And So is Love’, there’s an ongoing preoccupation with birds, and with blackbirds in particular: their beauty, their freedom, their fecundity, their ruthlessness, their fragility. It’s surely no coincidence that a dead bird plays a prominent role in that disconcerting “infant kiss” scene in The Innocents, a film of ghosts, family secrets and psychological horror which opens and closes with a soundtrack of birdsong; in short, a film which clearly exerted a profound influence on Kate’s imagination.

The bird fixation came to a head in Kate’s spectacular 2014 concerts, which included a complete staging of A Sky of Honey. The backdrop was awash with projected images of birds in flight; Kate sang her blackbird duet live; a puppet bird entranced the audience before meeting a grisly fate; and in the shamanic climax of the final number, Kate and her band transformed into birds before the audience’s eyes while giant trees smashed into the stage. It was dark, emotive, beautiful and strange, and it cut to the quick of everything that’s great about Kate. At the heart of her work, intertwined with the celebration of beauty and love and sensuality, there’s an ever-present edge of mania. It’s always been there, from ‘Wuthering Heights’ to ‘Sat In Your Lap’, from ‘Running Up That Hill’ to ‘King of the Mountain’ – those wild eyes darting left and right, those explosive Banshee shrieks, those softly obscure whispers, that hint of something dark and murderous lurking beneath the surface of life. All of this is fundamental, double-distilled Kate Bush. It’s what entranced that little boy all those years ago as he pored in wonder over that first album, and it’s what continues to entrance him today. “You stand in front of a million doors,” Kate reminds us in ‘How To Be Invisible’, “And each one holds a million more.” There are mysteries here: deep, dark mysteries that will never be solved. Nor should they be. That’s the magic of Kate.

This is an expanded version of an article which originally appeared in the Winter 2018 edition of Pride Life magazine. The 2018 remastered editions of Kate Bush’s albums are available in a variety of formats, including the CD box sets Remastered Part I and Remastered Part II. The anthology of Kate’s selected lyrics, How to Be Invisible, is published in hardback by Faber & Faber.